Port Ellen: the story of a lost distillery that didn’t stay lost

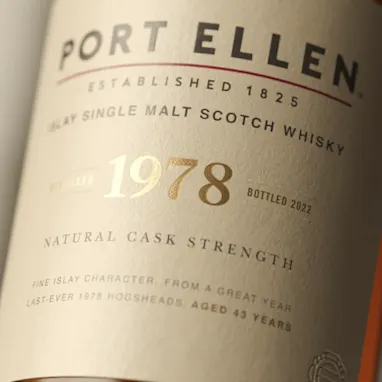

Port Ellen was heralded as one of the most iconic of the lost distilleries, remembered fondly by whisky lovers after shuttering in 1983. Before this closure, Port Ellen had won legions of fans across the world for its smoky, Islay whiskies produced since 1825.

That was until 2024, when it re-emerged thanks to a staggering £185M investment.

The reborn distillery, now welcoming keen visitors for immersive tours, pays homage to the past while looking ahead to the future, thanks to an ultra-modern design with an unobstructed line of sight through the glass stillhouse to the unrivalled coastline of Islay.

Two pairs of copper stills remain at the heart of the distillery. The first pair - the Phoenix Stills - are precise replicas of the original Port Ellen stills. The second - the Experimental Stills - will stand as a beacon for the pioneering spirit behind the art and science of an unparalleled whisky.

Part of the pioneering spirit behind the stills include the connection to the new Ten Part Spirit Safe, an innovative piece of distilling equipment that allows the Port Ellen whisky makers unprecedented opportunity for experimentation.

Typically, standard distillery spirit safes allow for three cuts of the spirit run – the head, the heart and the tails, but the Port Ellen Ten Part Spirit Safe allows multiple cuts to be drawn from the heart of the run, accessing previously unexplored flavours and characters, and takes the whisky-making art to new levels of intricacy and complexity, boosted by the expertise and attention of the on-site laboratory.

Brora: the resurrection of a Highlands icon

Having closed in 1983 during one of the most challenging periods for the industry, the reopening of Brora marked the first revival of a formerly lost name in whisky.

Brora’s closure in the 1980s followed a pattern for many whiskies that were used for blended scotches. Blenders used smoky whiskies judiciously, and at this time the blending requirements for medium and heavily peated whisky were being met by fewer distilleries. It was at this time that the Scotch industry as a whole closed down several distilleries, Brora included.

With meticulous attention to detail, the 202-year-old Brora stillhouse was taken down and rebuilt stone-by-stone exactly as it was when new in 1819, but now fit for another two centuries of production. At the heart of the Brora distillery restoration was the original pair of copper stills which travelled 200 miles across Scotland to be refurbished by hand by Abercrombie coppersmiths in Alloa.

Fully committed to recreating the processes before the closure, Brora uses traditional rake and gear mash tuns and uses malted barley from Glen Ord maltings - the exact same way it was done in the original run.

How a lost distillery from the past brought the industry into the future

It wasn’t just a loving attention to detail for Brora’s past that is notable about the revival, the project brings whisky’s future firmly into the picture. The restored distillery will now safeguard a sustainable future for Brora, with the installation of a biomass boiler powered by sustainably sourced wood chips from Northern Scotland.

How does a lost distillery come back? A timeline of events

Brora’s brand home host, Andrew Flatt, was able to share with us rare insight into just what went into bringing back this malts marvel.

The team had hundreds and hundreds of pages of handwritten ledgers, plans and drawings, stored in the Archives in Menstrie, in Elgin and at Clynelish, as well as in a former Exciseman’s hayloft. By sampling remaining historic stocks of Brora and using historic tasting notes, they began to piece together, with scientific precision, the distinctive Brora style that was so celebrated.

October 2018: Planning permission granted

November 2018: Copper pot stills reawakened and sent to Diageo’s Abercrombie coppersmiths in Alloa, Scotland

January 2019: Dr Jim Beveridge began undertaking historic tastings of old Brora liquid, the team worked through hundreds of pages of handwritten ledgers, plans and drawings, stored in the archives in Menstrie

April 2019: Removal of the Pagoda roof for repairs and refurbishment to the old kiln and new mash house

June 2019: Copper pot stills return to Brora

August 2019: Pagoda roof re-attached

October-November 2019: Installation of the Worm tubs and washbacks

March 2021: The first Mash and still runs

May 19, 2021: Brora opens its gates once again

July 2021: Brora welcomes guests to the new distillery brand home

Scotland’s iconic lost distilleries

Not every distillery has the Port Ellen or Brora ending. From hallowed names in the history of whisky to remnants of a bygone era, let’s rediscover some of the distilleries that have either closed for good, been demolished or changed how they operate.

Littlemill

Known for its floral, light Lowlands whisky, the lament of the lost Littlemill distillery is one shared by whisky lovers. With roots as far back as 1772, the Lowlands distillery was thought to be one of the oldest continuously licensed distilleries in Scotland.

For over 200 years, Littlemill innovated whisky. It had one of the first female distillery licencees, Mrs Jane MacGregor in 1823, and the invention of a new design of stills, replacing the traditional swan necks with rectifying columns, giving the production greater control of the whisky’s character.

Alas, Littlemill fell into trouble and was intermittently closed from 1984 to 1989, eventually falling silent altogether in 1994. Dismantled in 1997, the final tragedy would come when a fire would destroy the remaining buildings in 2004.

Rosebank

Rosebank - situated in Falkirk, part of the Lowlands region - is thought to date back as far as 1798. It was a rare wonder, celebrated as one of the few makers who were triple distilling their malts and was given the nickname of the ‘King of the Lowlands.’

Mothballed in 1993, Rosebank was bought and restored in 2017 by Ian McLeod Distillers.

Imperial

Dating back to 1897 before closing in 1998, Imperial is perhaps one of the lesser-known closed distilleries. This is because it was built primarily as a partner distillery to Dailuaine.

Imperial is notable, however, for being owned by most of the heavy-hitting names in the industry during its 100 year history. Owners included Diageo, John Walker and Pernod Ricard.

It was Pernod Ricard who would close it for good, and the distillery has since been demolished.

St Magdalene

The St Magdalene distillery was first known as Linlithgow, and was established in the mid 18th century by Sebastian Henderson.

The Lowlands distillery operated for over 200 years before closing in 1983, during one of the toughest periods for whisky distillers across Scotland. The distillery buildings have since been converted into private housing, but the malting barn and kiln have been preserved as a listed building.

Glenlochy

The Highlands distillery, Glenlochy, was founded in 1898, by David McAndie. The distillery took its water from the River Nevis, and sat in the foothills of the mountain from which the river takes its name.

Nothing remains of the original distillery except the Kiln building, which, thanks to its Charles Doig designed pagoda roof, was declared a historic building.

Fortunately, there are plenty of active distilleries that aren’t just keeping the doors open, they’re opening the world of whisky to thousands of new fans every year. Pay a visit to a distillery and discover why for yourself.