The History of Whisky

From ancient Greek technology to a cottage industry in Scotland, and finally a global phenomenon. The evolution of single malt Scotch whisky is a lesson in ingenuity, craft and the law of unintended consequences.

Who invented whisky?

From a classic Scotch Whisky, to Canadian whiskies, Japanese whiskies and more, there are plenty of places putting their own twist on our favourite spirit. But who actually invented the water of life? Well, that question leads to something of a spirited debate (pun intended).

In short - no one really knows. When it comes to a whisk(e)y as we know it today, both the Irish and Scots lay claim to be the originators. with early written records from Ireland in 1405 and Scotland in 1496, and both using the Gaelic phrase uisge beatha - 'water of life.'

While a definitive answer may never be known, what has become historical fact is how processes dating back to Ancient Greece helped shape the boom of the Scotch whisky industry as we know it today...

01

Ancient technology

The idea of distillation was not fixed until comparatively recently. The technology developed in numerous cultures, at different times, and came to mean different things to different craftsmen. For example, around 2500 years ago Greek sailors boiled seawater to get a drink. Around 2100 years ago, following the same process to get spirit from wine was common. The Greeks used a container with a small mouth, covered by a bowl.

Later, a tube and a vessel at the bottom to catch the spirit were added, giving us something similar to the stills we know today. Alchemists in Alexandria had several different still types by the 1st century A.D, using them as much as part of a ritual as for the elements they produced. In fact, the fire and spirit of distillation, the mystic and chemical, remained entwined for centuries – it was the Persians and the Arabs who began to move the process towards a science, using large, elaborate stills to experiment in the 9th and 10th centuries. Although these early chemists apparently succeeded in distilling spirits, they too were on a quest for the elixir of life.

02

Arrival in Britain

From the 12th to the 14th centuries, the process of distillation moved from the east to eastern Europe, and finally to the west. This was also the period of the Renaissance, the awakening of a new Europe based on the rediscovery of knowledge from the ancient Greek world – much of it scientific, much of it learned at second hand – an age of scientific discovery and invention. And also an age of new dangers: the practice of spirit distillation spread in the wake of the plague, which no doubt led many to seek new ways and medicines to alleviate suffering and ward off death.

The church, initially against distilled spirits, eventually allowed monasteries to house stills, with their herb gardens providing the ingredients for early medicines and liqueurs. As missionaries moved west, they took their technology with them.

03

Scotch whisky's origins - the official evidence

In August 1494 friar John Cor, a monk, possibly from St Andrews or the nearby Cistercian abbey at Balmerino or the Benedictine Lindores Abbey in Fife was allowed, ‘according to the King’s command’ to make ‘aquavite’ from 8 bolls - as much as 1,120 pounds - of malt. Although distilling had certainly gone on in Scotland prior to this date, particularly in the west and the islands of the Inner Hebrides, no earlier written record of it exists. And certainly, no one knows how Jon Cor made his aqua vitae.

04

The temperate King

Cor’s patron, King James IV, had come to the throne in 1488 having conspired with uncles and other nobles to bring about the death of his father. Then only a youth, he was 21 in 1494 when he issued the famous order to distil. James was Scotland’s great renaissance prince. Having inherited a divided kingdom, he had set about uniting Scotland under a single sovereign power and, in particular, sought to reduce the power of the Lords of the Isles who effectively held sway over much of Scotland’s west coast and western islands.

As a result, James travelled to the west and Islay in 1493 and again in 1494 – the first Scottish King to do so for a century. On Islay he may have witnessed distilling, or as an honoured guest might have been offered some of the precious elixir that it produced. A learned man, James came to patronise the early sciences, including medical research, of which distillation was a key practice. Born from the curiosity of a ‘sober and temperate’ king in magic and science, the rise of distillation comes to an end, as far as the records allow, just a suddenly with the end of his reign in 1513, at the Battle of Flodden.

05

The missing years

For nearly two hundred years, almost nothing is known about the development of distillation or the way that aqua vitae or whisky was used in Scotland. Duty was first imposed on spirits in Scotland in 1644, but taxation remained intermittent until the early eighteenth century. Untaxed, and therefore largely out of the sight of the public records, distillation in Scotland almost returned to the dark ages.

Knowledge of the process undoubtedly became widespread, fuelled by the dissolution of the monasteries at the reformation when the arts and sciences, which had been the preserve of monks, spread into local communities. War with France at the end of the 17th century put a block on trade in brandy and wine, and so also played a part in encouraging the domestic distilling industry to flourish.

06

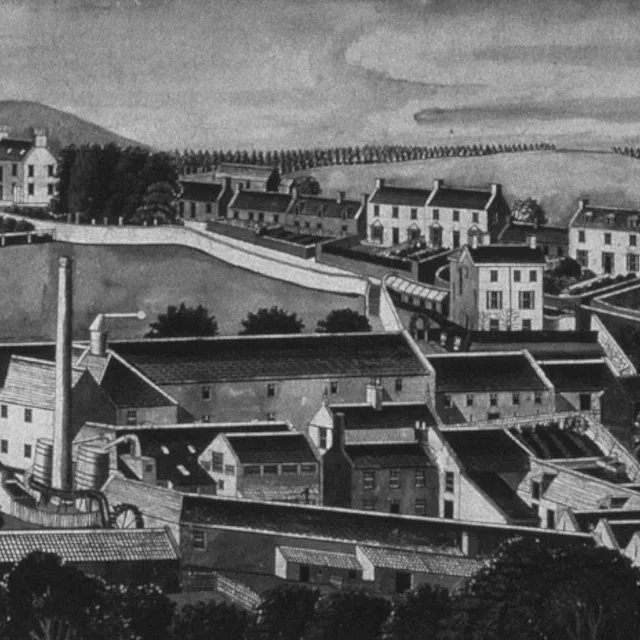

Cottage industry

Technical developments, increasing availability of metal, particularly copper, and the skills to work it, resulted in crudely wrought stills becoming widely available at this time. However, distillation was usually carried out largely on a very small scale, often in private domestic stills. Production methods would have been crude, and the quality of the spirit variable. There is no evidence that the spirit was matured at this stage in wood. Much was distilled from a mash of malt, but in some places, grain and malt were mixed together; in others, oats were used.

In times of scarcity, distillers would simply use whatever raw material was to hand. And very often spirit was drunk mixed with aromatics, milk or fruit, not just for recreational purposes, but to cure a variety of illnesses and maladies. It’s not whisky as we know it. It’s a liquid which takes its name from the Gaelic for the water of life - uisge beatha - but with many definitions.

07

Going underground

Whatever they made or mixed it with, the whisky was popular. And increasing popularity attracted the attention of the Scottish Parliament, which introduced the first taxes on malt and whisky with the Excise Act of 1644. But it was The Act of Union with England in 1707, the highland clearances and other measures to suppress rebellious Scottish clans which saw a change in the culture of Scotland, and Scotch whisky. Coupled with a law prescribing the minimum size of still, these changes drove farmer distillers underground.

What followed was a long and violent struggle between small-scale distillers, with their cornerstone of Scottish culture and commerce, and the royal excisemen or ‘gaugers’. Smuggling became standard procedure and illicit distilling flourished for some 150 years: clandestine stills were hidden in the Glens, smugglers and villagers worked out secret codes of warning and transport, even church ministers stored and transported the stuff. By the 1820s more than half of the whisky being drunk in Scotland was done so without payment of duty.

08

The Excise Act

Leading landlords saw the problem and the opportunity. If their tenants could make money from a covert, badly-managed and inefficient process, then how much more might they be able to make from an efficient legal one? They petitioned the Government to change the law and make it profitable to produce whisky legally. In 1823 the Excise Act was passed, which allowed the small-scale the distilling of whisky in return for a licence fee of £10, and a set payment per gallon of proof spirit. Smuggling died out – though not without a fight – over the next ten years, and illicit distillers changed their colours.

The Cummings of Cardow, for example, illicit farm distillers for at least a generation, replaced their red flag which had long been used to warn of the exciseman’s approach with a licence in 1824. Today, many distilleries stand on sites used by the smugglers of old. In short, driving the production underground caused the smugglers to develop a ready market for whisky: and The Excise Act created an industry overnight.

09

Aeneas Coffey, the Walkers and Phylloxera

This industry was to witness three incredible pieces of good fortune following the Excise Act. First, in 1830 Aeneas Coffey invented the Coffey or Patent Still which enabled continuous – as opposed to batch – distillation to take place. This led to the production of the lighter-flavoured grain whisky which, when blended with the more fiery malts, extended the appeal of Scotch whisky to a broader market.

This demand for blended Scotch drove production at distilleries higher, and more importantly imposed stringent quality criteria that the distillers had never before encountered. It was the rise of the great blending houses to seal the destiny of the industry. One such blender was John Walker, a grocer from Kilmarnock, who found himself well-positioned to take advantage of these changes. His skill in blending created a whisky of high quality and his business acumen saw the birth of one of the first whisky brands as we know them. Walker’s son Alexander carried on the family tradition, transforming a local grocery firm into an international whisky business with few, if any, rivals.

Fifty years later, with the market for Scotch firmly established, the Phylloxera beetle began feasting on the grapevines of France, effectively halting wine and cognac production by 1880. Stocks of both dwindled to almost nothing, and Scottish distillers and blenders were there to fill the void in the cellars of the rich. By the time the French industry recovered, Scotch whisky had replaced brandy as the preferred spirit of choice for the upper classes.

10

Global phenomenon

Despite a crash towards the end of the 19th century, stiff competition from other whisky-producing nations, two world wars, a great depression and US Prohibition, Scotch whisky has survived to become the world’s number one spirit of choice. Today it is enjoyed by people of all backgrounds, creeds and clans: a spirit used to toast business deals, holidays, homecomings and every other little special occasion in 200 countries.